ENERGY

One of the main pillars of CERN’s efforts to minimise its impact on the environment is the pursuit of actions and technologies aimed at energy savings and reuse, with a commitment to operate the accelerators and related infrastructures as efficiently as possible.

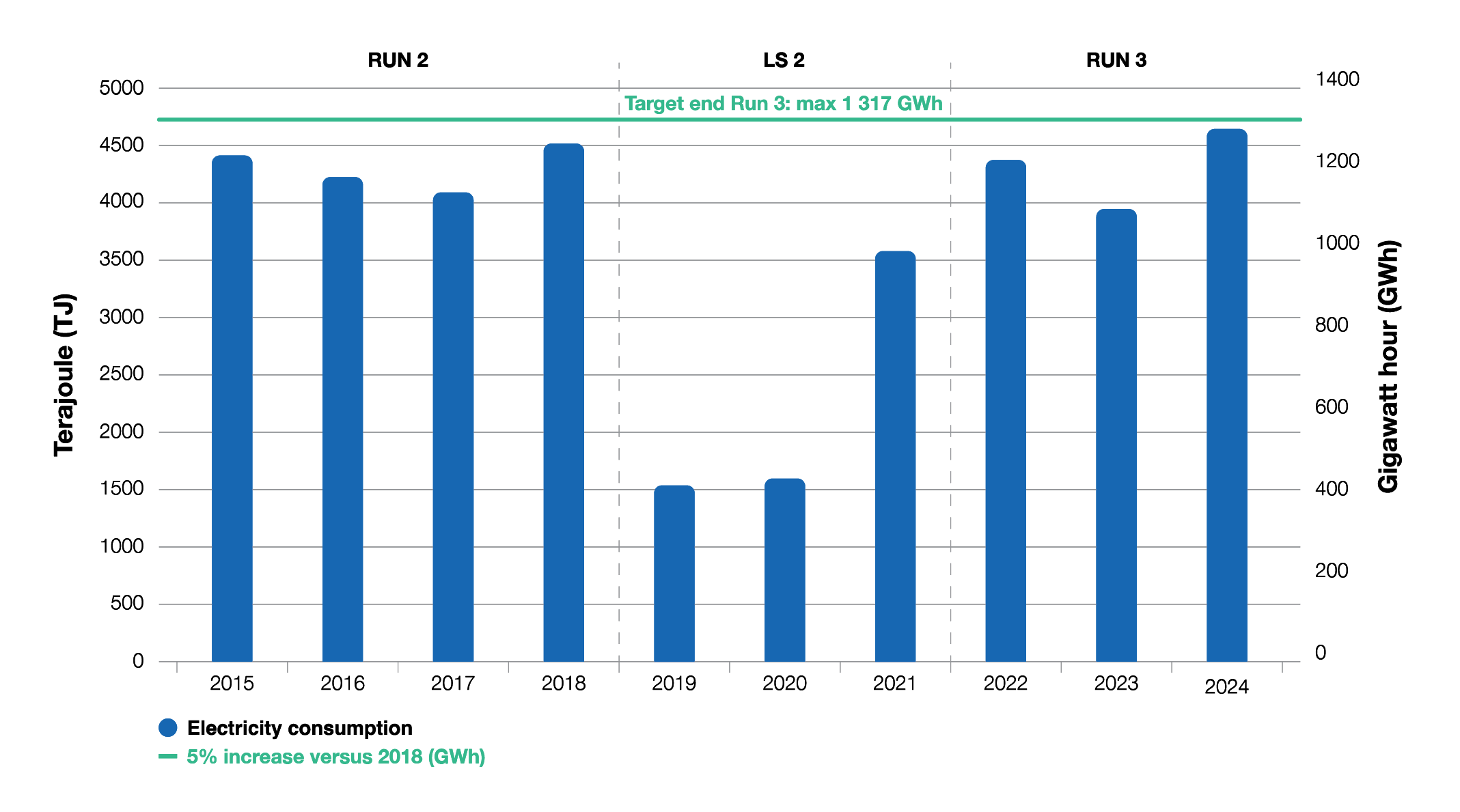

A key objective is to limit the increase in electricity consumption to no more than 5% above 2018 levels until the end of Run 3.

POWERING SCIENCE

CERN’s unique array of accelerators, detectors, computing and other technical infrastructure is primarily powered by electricity, accounting for about 95% of CERN’s total energy use. Its flagship accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), accounts for some 55% of the total consumption. In 2023 and 2024, which were both operation (‘Run’) years, CERN’s electricity consumption amounted to 1 096 GWh (3 946 TJ) and 1 290 GWh (4 645 TJ), respectively. In 2023, in the wake of the energy crisis, accelerator operation was reduced by 20% by extending the Year End Technical Stop (YETS) to 19 weeks, leading to savings of about 70 GWh of electricity.

Specific projects to renovate the ventilation and cooling systems of the accelerators are under way with a view to achieving energy gains of 8 GWh per year. In this vein, during the reporting period, the ventilation system that cools the Meyrin data centre was fully renovated, including installation of variable-speed drives. Since 2022, to further foster energy savings, the LHC cryogenic installations have been operating in “eco mode” whenever possible, leading to energy savings of up to 20 GWh per year.

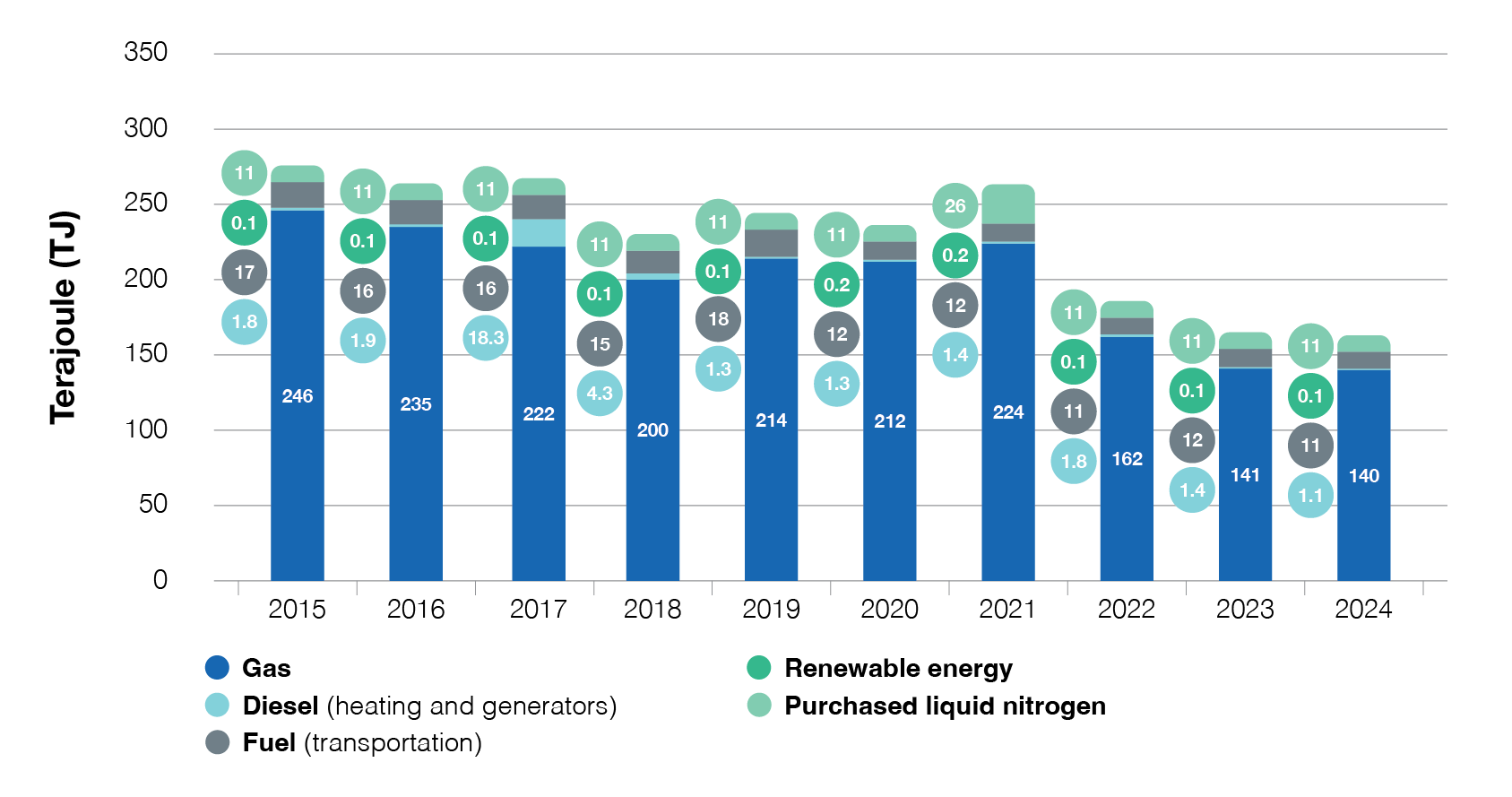

The Laboratory also uses natural gas for heating, fuel for its fleet of vehicles and diesel for emergency generators, and consumed 43 GWh (154 TJ) of fossil fuels in both 2023 and 2024. It also uses commercial liquid nitrogen for cooling and small amounts of photovoltaic energy produced on the CERN site.

CERN ELECTRICITY CONSUMPTION 2015 – 2024

Runs refer to the years in which the accelerators are in operation, with annual year-end technical stops and additional technical stops as and when necessary. Outside these periods, the accelerator complex enters ‘long shutdowns’ for essential maintenance, renovation and upgrades. In 2023, a technical issue led to the stop of the machine for one month, with an impact on electricity consumption.

Note: following the award of the ISO 50001 certification, the energy data calculation process has changed from a monitoring-based approach to an invoicing-based approach, incurring very small variations with respect to previous years’ data, which has been updated in the graph accordingly. Notably, the target for the end of Run 3 has been recalculated as 1 317 GWh, compared to 1 314 GWh previously.

CERN’S ENERGY CONSUMPTION – OTHER CATEGORIES OF ENERGY 2015–2024

In line with ISO 50001 certification requirements, notably the transition to more accurate invoice-based data collection, all values have been adjusted for previous years.

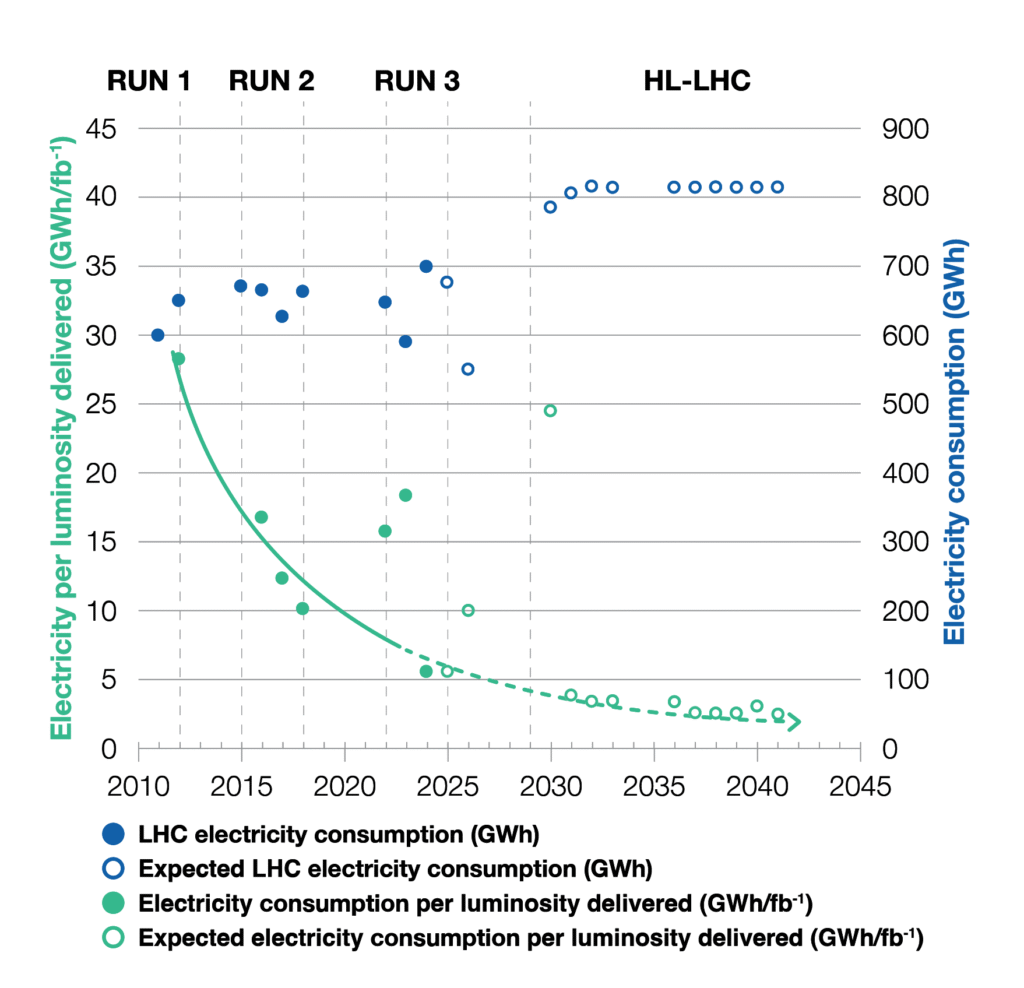

CERN’s frontier physics programme relies upon ever more data being delivered to the experiments, which is measured in the LHC by a parameter known as luminosity. Higher luminosity increases the number of proton-proton collisions, hence data collection, enhancing statistical precision and the potential for discoveries. However, it can also lead to higher electricity consumption.

In addition to limiting the increase in electricity consumption to 14% during High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) compared with the consumption in Run 3, CERN is committed to improving energy efficiency by maximising the luminosity delivered per unit of energy consumed. Between Run 1 and the end of Run 2 (i.e., from the start of the LHC to 2018), the LHC’s efficiency in this regard tripled. With the HL-LHC, a further improvement by a factor of four is projected.

ELECTRICITY INTENSITY OF THE LHC

Quantity of electricity used to run the LHC per unit of luminosity delivered, showing that less and less electricity has been needed over time to produce the same amount of data and, hence, scientific output.

During the year after each long shutdown (LS), while the accelerator is being brought back online and progressively ramped up, the luminosity delivered is not at its maximum – as seen in 2022 and expected for 2030. The outliers in 2023 are due to the technical issue that led to the stop of the LHC machine for one month, with an impact on electricity consumption. The outliers forecast for 2026 are due to the partial operation of the machine (LS starting mid-year).

CERN’S ENERGY STRATEGY

CERN’s Energy Management Panel (EMP), established in 2015, drives CERN’s energy strategy, which spans three pillars: increase efficiency, use less, and recover waste energy. CERN’s energy management approach is further strengthened by the CERN Energy Policy (published in 2022), a dedicated energy coordinator and the enlarged EMP, which meets regularly to include all of CERN’s activities beyond the accelerator complex. Furthermore, CERN collaborates closely with its Host States through the tripartite committee for the environment (Comité Tripartite pour l’Environnement – CTE), which was established in 2007, and with its grid operators and electricity suppliers.

Energy procurement currently represents 5 to 10% of CERN’s annual budget when the accelerators are running, and less during shutdown periods. Electricity is primarily procured from France, whose energy grid mix is more than 95% low carbon (2024).

In the context of CERN’s Environmentally Responsible Procurement Policy Project (see Procurement and Materials), procurement guidelines for equipment, products and services have been established in which energy performance over the planned or expected operating lifetime is one of the criteria. This applies to the procurement of any item where power exceeds 500 kW or annual energy consumption exceeds 5 GWh.

ISO 50001 certification

The ISO 50001 standard provides guidance and tools to improve energy performance and integrates energy management into overall efforts to improve quality and environmental management.

(Image: AFNOR)

CERN was awarded the ISO 50001 certification on 2 February 2023 for a period of three years, covering the entire perimeter of the Organization across all sites, as well as all activities and energies. In this context, mandatory annual surveillance audits are carried out by the French national organisation for standardisation, AFNOR. Successful external and internal audits (two of each) were carried out in the reporting period; the results confirmed that the organisational structure and technical measures implemented by the Organization meet and often exceed the required standards and are effective in optimising energy management processes.

ALTERNATIVE ENERGY SOURCES

Diversifying its energy mix, notably with photovoltaic energy is an important aspect of CERN’s responsible energy management framework. An extensive study of the use of the roofs and car parks on CERN’s sites for installing photovoltaic panels was performed in the reporting period, and the associated energy and cost benefits were found to be minimal. Consequently, in the search for suitable solutions to achieve its objective of covering part of its electricity needs through renewable energy, CERN signed three physical power purchase agreements (PPAs) with energy providers in France at the end of 2024. These PPAs will provide solar power covering approximately 140 GWh of CERN’s annual electricity consumption from 2027 onwards (see In Focus). This represents 30% of the electricity consumption during shutdown periods and about 10% during operation (‘Run’) years.

On a smaller scale, the CERN Science Gateway building on the CERN site, which was inaugurated in October 2023, comprises 1855 solar panels each measuring two square metres. These panels cover the building’s energy needs, and inject any surplus photovoltaic energy into CERN’s grid.

OPTIMISING ENERGY ACROSS THE CAMPUS

The energy that the Organization needs to power its buildings and general infrastructure represents about 10% of its total consumption. Continuous optimisation efforts are underpinned by an extensive consolidation programme that spans five years and is reviewed annually in the case of the heating, electrical, ventilation and air conditioning infrastructure. The Office Cantonal de l’Energie (OCEN) in Geneva, Switzerland, notably contributes to financing such consolidation work on the Meyrin site.

Specific measures further support CERN’s efforts to minimise energy use. These measures include delaying the annual start-up of district heating, adapting it to the weather conditions and reducing the temperature of the boilers, representing gas savings of 15 GWh per year compared to pre-2022 levels. A campaign was launched in 2023 to replace halogen lamps with energy-efficient LEDs in tertiary buildings. By the end of 2024, the project was 95% complete with some 50 000 lamps replaced, resulting in total electricity savings of approximately 3 GWh per year.

HEAT RECOVERY

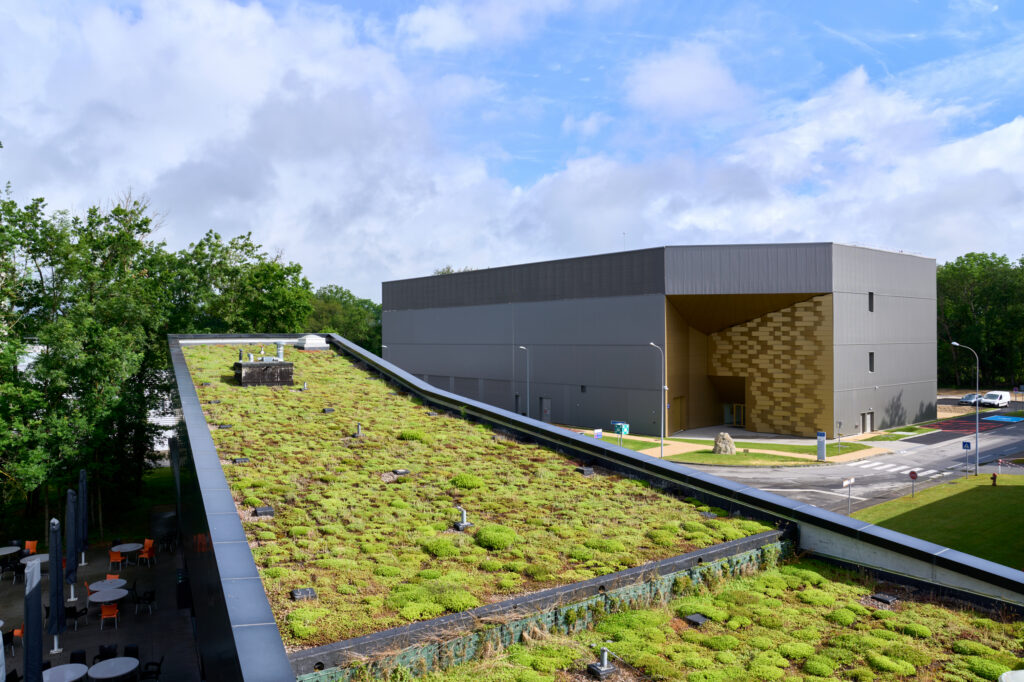

Waste energy recovery is a priority for the Organization, with several dedicated projects at various stages of advancement. These are critical to achieving considerable gas savings by 2030 of some 60% compared to 2018. In February 2024, CERN inaugurated its new state-of-the-art data centre located on the Prévessin site. The new building is equipped with an efficient heat-recovery system that will be connected up in the winter of 2026/2027 and will contribute to heating all the buildings on the Prévessin site. Another project on the Meyrin site, consisting in recovering heat from the LHC Point 1 cooling towers, got under way during the reporting period. Both projects represent total energy savings of some 25–30 GWh per year as of 2027.

At LHC Point 8 near Ferney-Voltaire in France, the final stage of the work to connect up the equipment needed to heat a neighbouring residential area was completed on CERN’s side at the end of 2024. It is estimated that, as of 2026, some 20 GWh per year will thus be recovered from the cooling towers at Point 8.

COMPUTING AND IT INFRASTRUCTURE

The High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) project is expected to deliver a tenfold increase in the amount of physics data collected during its period of exploitation (scheduled to end in 2041) compared to the original LHC design, leading to a considerable rise in the computing capacity required by the experiments. CERN is committed to balancing the associated rise in energy needs through strategic planning aimed at optimising the computing infrastructure and its hardware and software tools. Ongoing efforts focus on modernising code, optimising its performance for the latest hardware, and improving data management. By developing innovative approaches to key computing tasks – including machine learning and related technologies – CERN is progressing in reducing the overall computing resources required, helping to limit energy consumption growth.

The new data centre in Prévessin, inaugurated in February 2024, is designed to provide up to 12 megawatts (MW) of power capacity for computing, to be deployed in three phases in line with CERN’s evolving needs. The upgrade to Phase 2 (8 MW) is scheduled for 2027/2028 to meet the demands of the first run of HL-LHC (Run 4). The data centre targets a power usage effectiveness (PUE) of around 1.1 — a level of energy efficiency significantly better than the industry average, where large data centres typically operate at PUEs of 1.5 and new facilities achieve between 1.2 and 1.4 (with a score closer to 1.0 indicating higher efficiency). The Meyrin data centre, with a PUE of below 1.5, is housed in a 1970s building that was not originally designed for modern computing equipment, making further optimisation challenging. It will continue to operate, focusing mainly on storage activities that are better suited to its lower power density. Plans to enhance its power efficiency and improve sustainability, for example by reducing the number of UPS systems and batteries, are under discussion.

Growing awareness across computing and physics communities, along with rising energy costs and regulatory requirements, are driving a stronger commitment to sustainable computing practices. The WLCG collaboration at large is engaged collectively in assessing new methods and technologies to minimise environmental impact. In this vein, the first WLCG sustainability workshop was held in December 2024 to further foster collaboration, share best practices and drive efficiency across the network. The first main objectives include setting up a framework to collect information related to energy efficiency, to facilitate the use of more energy-efficient hardware where possible and to develop and promote a sustainability plan to improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon footprint. The objectives cover software, computing models, facilities, and hardware technology and lifecycle.

| CERN’s main objective is to provide extensive data to scientists in order to further fundamental physics research and hone our understanding of the Universe. This data, of the order of ~200 Petabytes in 2024 for the LHC experiments only, is generated mainly by the particle beam collisions captured by the experiments. The Worldwide LHC Computing Grid (WLCG) is a global collaboration bringing together CERN and some 160 computing centres in more than 40 countries to link up national and international computing infrastructures and thus provide the global computing resources necessary to store, distribute and analyse these vast amounts of data. The energy consumption figures provided in this report relate exclusively to facilities owned or operated by CERN. |

GOALS FOR 2030

By 2030, CERN aims to continuously improve the Organization’s energy performance by minimising the energy required for its activities, enhancing energy efficiency and recovering waste energy. During Run 4 (2030–2033), the collision rate will increase by a factor of five compared to the nominal LHC design and this increase could reach a factor of 7.5 when the ultimate performance starts to be reached in Run 5. Despite this, CERN is committed to limiting its electricity consumption to 1.5 TWh per year, representing an increase of 14% compared to the original target for the end of Run 3. The objectives also include covering 10% of electricity needs through power purchase agreements (PPAs) based on renewable energies and reducing gas consumption by 60% compared to 2018 (on a weather-normalised basis).

IN FOCUS

Nicolas Bellegarde is CERN’s energy coordinator.

— What steps did CERN take to evaluate the potential use of solar energy to meet part of its electricity needs?

NB: Diversification of energy sources is part of the Organization’s energy strategy, in line with the ISO 50001 requirements. Photovoltaic power has been under consideration for some time and we first revisited whether the CERN campus infrastructure, through use of its roofs and car parks, could be leveraged to install sufficient solar panels to meet 10% of our electricity needs. A study was undertaken in collaboration with Swiss Solar City, a company that specialises in equipping car parks and roofs with solar panels. This revealed that the potential accessible areas at CERN spanned some 100 parking spaces and a further 5000-10 000 m2 of roof surfaces, with no tangible technical or economic benefits. We therefore continued our search with external partners in the form of power purchase agreements (PPAs).

— What is the scope of the resulting PPA contracts signed at the end of 2024?

NB: The PPAs concerned will secure the supply of electricity from planned solar power plants in the Lozère, Bouches-du-Rhône and Var departments in southern France, giving access to a total area of approximately 90 hectares (900 000 m2) of solar panels, equivalent to more than 120 football pitches. This is equivalent to about 40% of CERN’s fenced area; a project of this scale would have been unfeasible on the CERN site. The aim is that CERN should start to receive electricity from these plants as of January 2027. CERN has committed to purchasing electricity produced by the solar plants, representing a total of 95 MW peak power and a supply of 140 GWh/year over a period of 15 years.