WATER AND EFFLUENTS

Water is a critical resource for CERN’s operations, particularly for cooling its accelerator complex. The Organization is committed to the continuous improvement of its installations in order to minimise water consumption and allow the quality of its effluents to be monitored.

MANAGING WATER CONSUMPTION

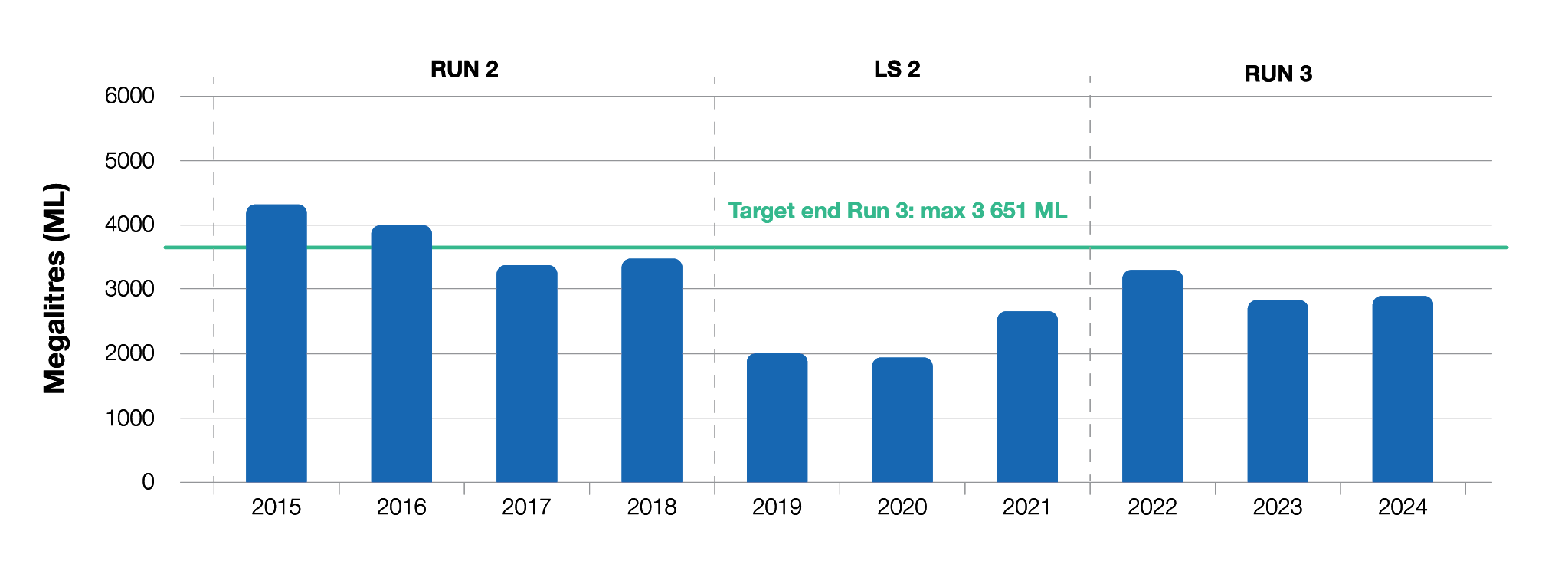

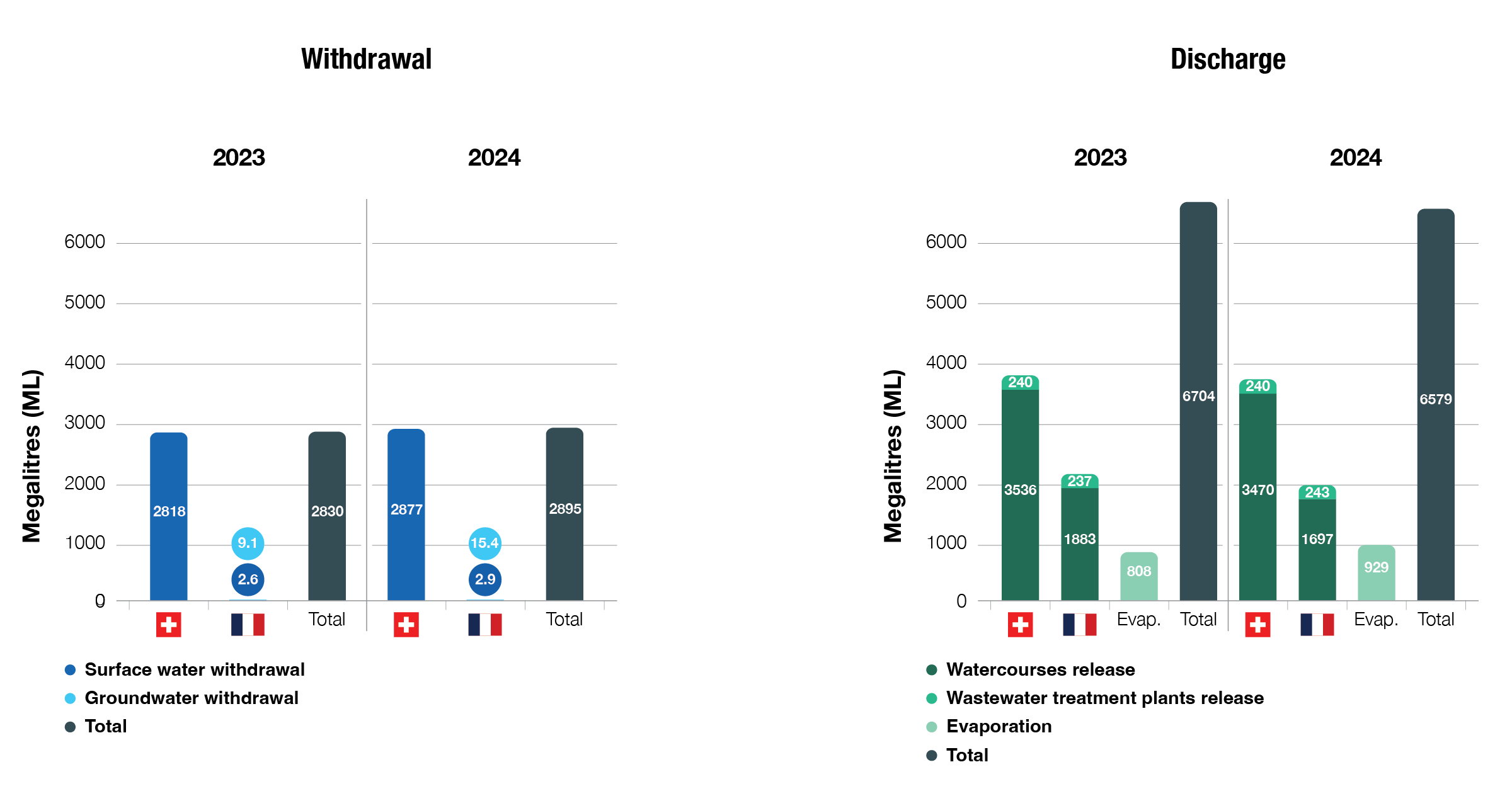

The majority of CERN’s water consumption is due to its “industrial” activities, mainly the cooling of the accelerator complex, while a smaller fraction is used for sanitary purposes. 99% of CERN’s water supply comes from the local Lac Léman and is provided by Services Industriels de Genève (SIG); the small remaining fraction comes from groundwater provided by the Régie des Eaux Gessiennes in France and is mainly used for sanitary and drinking purposes on the LHC sites. The water is of drinking quality and is used as it is or else demineralised. In 2023 and 2024, which were both operating periods, CERN’s water consumption was 2830 megalitres and 2895 megalitres, respectively. These figures are lower than for the previous reference operation year, 2018 (3477 megalitres), a reduction that represents an outstanding achievement.

The tripartite environment committee meets regularly to allow CERN to exchange on water protection issues with the local Host State authorities, based on input from CERN’s water monitoring programme (see Management Approach). CERN’s environmental emergency preparedness framework includes intervention plans to address any incidents that may arise, along with procedures to mitigate the potential consequences for local watercourses and to notify the relevant Host State authorities and emergency services. Their effectiveness was tested and demonstrated during the reporting period, with a significant leak occurring in CERN’s water distribution network, caused by drilling work. The incident was resolved in collaboration with the local services and authorities. No fine or sanction was incurred in the reporting period (see Environmental Compliance and Management of Hazardous Substances).

OPTIMISING THE WATER INFRASTRUCTURE

CERN is committed to keeping the increase in its water consumption below 5% up to the end of Run 3 (baseline year: 2018). Despite an increase in cooling needs anticipated with the upgrade of facilities, CERN is engaged in a continuous programme of improvement of its water infrastructure, optimising cooling towers and water networks to reduce effluent water, improve its quality and minimise water consumption. A good example of achievements in this area is the North Area cooling tower recycling plant, which, since commissioning in 2018, has undergone continuous optimisation to enhance yield and reduce water consumption. In 2023, more than 14 000 m³ of blowdown water was treated and recycled and reintegrated into the cooling towers.

The next major project concerns the renovation of the Antiproton Decelerator (AD) cooling infrastructure, which will lead to marked water consumption reductions as of 2027.

In the reporting period, CERN’s two demineralised water production units, which feed the water networks of the various sites, were modified and optimised; renovation works on one of the two units further improved yield and contributed to the reduction of CERN’s water consumption. The modifications led to a total reduction of water consumption of 12 000 m3 in 2024, while the renovation project is expected to bring a further reduction of some 20 000 m3/year.

During the 2024 Year End Technical Stop, CERN implemented an automated system to streamline the monitoring and management of demineralised water ratios in its cooling circuits. This innovation aims to prevent overconsumption while maintaining optimal system performance. Initial tests have demonstrated promising results, and further dedicated trials are under way on selected circuits. These efforts are paving the way for a potential full-scale deployment across all circuits.

CERN’s Technical Galleries Consolidation programme, launched in 2021 and spanning two decades, focuses on renewing key services such as the hot water distribution, drinking water and firefighting networks. Significant improvements in reliability, energy efficiency and water quality have been achieved. On the Meyrin site, the drinking water and firefighting networks in the West Area were completed, with over 3 km of new piping installed. Work has begun on upgrading the hot water circuit to reduce energy loss, and is due to be completed by 2028. Future renovation work to ensure that CERN’s infrastructure meets modern standards will be aligned with the constraints of LS3.

In the next five years, two new cooling towers for the HL-LHC project and one for the CMS detector upgrade will be installed and will be operational towards the end of LS3.

WATER RELEASE AND EFFLUENT QUALITY

The Organization discharges rainwater, infiltration water and cooling water into local watercourses, some of which are small and sensitive to the quality of the effluents they receive. CERN continuously monitors the quality of its effluents in accordance with CERN-defined criteria that comply with Host State regulations and conducts regular sampling of the adjacent rivers to assess the impact of its operations. The results are provided quarterly to the Host State authorities.

A large part of the water used for cooling the accelerators is evaporated by CERN’s cooling towers. A fraction is released as effluent water, which contains the residues of treatments to prevent scaling, corrosion and bacterial growth, including legionella. In 2024, CERN renewed its water treatment contract, which was used as an opportunity to eliminate the use of phosphate in such treatments.

A major project to consolidate the cooling towers started in 2016 with a view to improving the quality of effluent releases. As part of this project, the addition of demineralised water after the recycling process to allow blowdown water to be reused in cooling towers is proving effective in reducing releases into the neighbouring watercourses. Between 2018 and 2023, the total volume of effluent releases from the cooling towers on the Meyrin site was reduced from some 81 000 m3 to just over 52 000 m3. The next long shutdown, starting in 2026, will see the completion of the project to modify the cooling circuits, 70% of which were modified during LS2. The remaining 30% are the larger LHC and SPS circuits; a study was launched in the reporting period with a view to installing a new cooling water recycling plant at LHC Point 1 during LS3. The release of residual effluents from the recycling plant directly into the sewage network will limit the impact on the Nant d’Avril river.

Rainwater management on the CERN sites is another priority for the Organization, in line with the Masterplan 2040. According to the present strategy, all new projects affecting the Swiss watershed of the Meyrin site include rainwater retention solutions, either on the roof or in the form of basins that are buried or, where possible, in the open air. Retention basins are also a key feature of the Charter of the Nant d’Avril, signed in 2020, which aims to regulate the flow from the Meyrin site and prevent environmental incidents that could impact the watercourse.

CERN has implemented several rainwater retention initiatives to manage water runoff and improve water quality. On the Prévessin site, the retention basin built in 2020, located downstream of the site that includes a hydrocarbon separator for treating accidental releases, has proven its effectiveness in regulating the flow and managing the quality of water releases. An additional basin on the Prévessin site with a capacity of 3 000 m3 was finalised in 2023 to manage stormwater runoff surplus and help to regulate the flow of release into the nearby Lion river. In the reporting period, it was decided to build two additional basins on the Meyrin site, namely a 2 800 m3 storage tank to collect rainwater under one of the hostel buildings and a 1 000 m³ vegetated pond designed to regulate rainwater flow, enhance biodiversity and limit the impact on the Nant d’Avril river.

Data shown for discharge into watercourses includes infiltration water, rainwater and cooling tower blowdown. Evaporation (Evap.) refers to the water evaporated by CERN cooling towers.

GOALS FOR 2030

Over the period until 2030, CERN aims to optimise the Organization’s water consumption, increase water retention and improve the quality of effluents released into watercourses.

CERN’s objective is to keep its annual water consumption below 3 600 megalitres despite the growing demand for cooling water, to reduce the zinc load in effluents to the Nant d’Avril river in Switzerland by 90% and to increase the water retention volume available on CERN sites.

In focus

Michela Lagioia is an HVAC engineer in the Site and Civil Engineering department’s Site Asset Management team.

— What was the motivation behind upgrading the cooling of nine buildings on the Meyrin site?

ML: This project is part of the recurrent consolidation plan for the CERN site, which spans ten years and is reviewed annually. These particular buildings, constructed between 1961 and 1967, have an outdated cooling system, with over 20 units requiring frequent maintenance and generating high operational costs. The system comprises a cooling plant that supplies several workshops and laboratories, including the CO2 laboratory, and a plasma cell for the AWAKE experiment, as well as offices. The goal was to replace it with a centralised, modern system to reduce the environmental impact, improve energy efficiency and simplify maintenance. The chillers have been sized to take into account the existing needs, as well as possible future expansion needs. This upgrade supports CERN’s environmental objectives while ensuring reliability for the labs, workspaces and workshops in these buildings.

— Can you describe the key improvements achieved through this project?

ML: The project was completed in three phases: installing a chilled water loop, centralising cooling production and upgrading the distribution systems. The new centralised cooling plant, which has been operational since summer 2024, supplies chilled water to laboratories and offices via an efficient network. This has significantly lowered energy consumption, reduced maintenance needs and enhanced overall reliability, marking a major step forward in modernising CERN’s infrastructure.